Mukhopadhyay T. (2008). Whether monetary empowerment leads to gender empowerment or not: case studies in the context of micro credit programmes in India. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 18-37. ISSN 2029-0365. [www.ScholarArticles.net]

Author:

dr. Tilak Mukhopadhyay, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR), India

Abstract

The paper deals with the relationship between monetary empowerment and gender empowerment. The objective of the paper is to determine whether and to what extent participation in Self Help Groups (SHGs) impacts the empowerment of women members. After briefly discussing the history and structures of Self Help Groups the paper explains the relationship with some case studies. From the case studies, it is evident that the relationship between economic empowerment and gender empowerment does not go in same line in all the cases. The linkage effect of economic empowerment is not readily transformed into decision making power for women in most of the cases. Self Help Groups can be one way to achieve some level of gender empowerment, but in Indian society the gender empowerment depends on much more complex factors rooted in various demographic and religious factors. So the success rate to achieve gender empowerment through micro credit schemes is not very significant in Indian society. The paper proposes a dummy variable model to estimate the level of empowerment of a woman member before and after joining a micro credit scheme.

Introduction

The concept of development and method of its execution have become the most important socio-economic and political issues at this present time. As an obvious consequence, various debates about the concept of development have already emerged across the globe and they have captured the lion share of intellectual attention in the field of economic literature. The concept of a Self Help Group (SHG) and its various practices were always subjected to appreciation and criticisms from the various schools of thoughts. Impact and role of Self Help Groups had always invoked various new ideas regarding the question of development on the course of transition of the society. This article deals with a particular aspect of Self Help Groups and implementation of micro credit schemes in the rural India. It investigates the question of gender empowerment through the monetary empowerment of rural women in India. For closer look at this issue, case studies from various states of India are analyzed further in the article in order to find out whether the micro credit schemes and the Self Help Group as an Institution promote achievement of gender empowerment or not. The prime question of the paper is: whether there is a relationship between monetary empowerment and gender empowerment. The objective of this paper is to determine whether and to what extent participation in Self Help Groups impacts the empowerment of women members. Taking into consideration the great importance that is being given to the group approach while conceptualizing and implementing any programme for the rural poor, especially women, this study becomes both essential and relevant. More specifically, in this work it is sought to explore if the SHG approach has been successful in the empowerment of rural women living in the highly patriarchal and traditional societies of the different rural states of India. The article provides several case studies in different states of India and analyzes whether there is any impact of micro credit schemes on the aspect of decision making of rural women in India. For analyzing these case studies, the following research questions were formulated: Does participation in SHGs increase woman’s influence over economic resources and participation in economic decision making? Is there an increase in woman’s influence in decision making in the household? Does participation in SHGs increase woman’s participation and influence in social, community and political activities? Is there any change in the attitude of the husband/household/ community regarding women’s empowerment?

A brief history of microfinance in India

The post-nationalization period in the banking sector, circa 1969, witnessed a substantial amount of resources being earmarked towards meeting the credit needs of the poor. There were several objectives for the bank nationalization strategy including expanding the outreach of financial services to neglected sectors (Singh, 2005). As a result of this strategy, the banking network underwent an expansion phase without comparables in the world. Credit came to be recognized as a remedy for many of the ills of the poverty. There spawned several pro-poor financial services, supported by both the State and Central governments, which included credit packages and programs customized to the perceived needs of the poor. While the objectives were laudable and substantial progress was achieved, credit flow to the poor, and especially to poor women, remained low. This led to institution-driven initiatives that attempted to converge the existing strengths of rural banking infrastructure and leverage this to better serve the poor. The pioneering efforts at this were made by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), which was given the tasks of framing appropriate policy for rural credit, provision of technical-assistance-backed liquidity support to banks, supervision of rural credit institutions and other development initiatives. In the early 1980s, the Government of India launched the Integrated Rural Development Program (IRDP), a large poverty alleviation credit program, which provided government subsidized credit through banks to the poor. It was aimed at enabling the poor to use inexpensive credit to finance themselves over the poverty line. Also during this time, NABARD conducted a series of research studies independently and in association with MYRADA, a leading non-governmental organization (NGO) from Southern India, which showed that despite having a wide network of rural bank branches servicing the rural poor, a very large number of the poorest of the poor continued to remain outside the fold of the formal banking system (MYRADA, 2002). These studies also showed that the existing banking policies, systems and procedures, as well as deposit and loan products were perhaps not well suited to meet the most immediate needs of the poor. It also appeared that what the poor really needed was better access to these services and products, rather than cheap subsidized credit (NABARD, 2005). Against this background, a need was felt for alternative policies, systems and procedures, savings and loan products, other complementary services, and new delivery mechanisms, which would fulfil the requirements of the poorest, especially of the women members of such households. The emphasis therefore was on improving the access of the poor to microfinance rather than just micro credit. To meet the need for microfinance from the poor, the past 25 years has seen a variety of microfinance programs promoted by the government and NGOs. Some of these programs have failed and the learning experience from them has been used to develop more effective ways of providing financial services. These programs vary from regional rural banks with a social mandate to Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs). In 1999, the Government of India merged various credit programs together, refined them and launched a new programme called Swaranjayanti Gram Swarazagar Yojana (SGSY). The mandate of SGSY is to continue to provide subsidized credit to the poor through the banking sector to generate self-employment through a Self Help Group approach and the program has grown to an enormous size. The idea of microfinancing may be elucidated using quotation of Kofi Annan, the former secretary general of the United Nations (UN), of 29 December 2003: “The International Year of Micro credit 2005 underscores the importance of microfinance as an integral part of our collective effort to meet the Millennium Development Goals. Sustainable access to microfinance helps alleviate poverty by generating income, creating jobs, allowing children to go to school, enabling families to obtain health care, and empowering people to make the choices that best serve their needs. The great challenge before us is to address the constraints that exclude people from full participation in the financial sector. Together, we can and must build inclusive financial sectors that help people improve their lives”. Noble Peace prize winner Md.Yunus started his experiment with the micro credit programme in 1976 and eventually he formed The Grameen Bank which has more than 3.2 million borrowers (95 percent of whom are women), 1,178 branches, services in 41,000 villages and assets of more than 3 billion USD (Yunus, 2004). The prime objectives of this institution are nearly the same as those indicated by the UN. MFIs have also become popular throughout India as one form of financial intermediary to the poor. MFIs exist in many forms including co-operatives, Grameen-like initiatives and private sector MFIs. Thrift co-operatives have formed organically and have also been promoted by regional state organizations like the Cooperative Development Foundation (CDF) in Andhra Pradesh (Reddyand Manak, 2005). The Grameen-like initiatives have followed a business model offered by the Grameen Bank. Private sector MFIs include NGOs that act as financial services providers for the poor and include other support services but are not technically a bank as they do not take deposits. Recently, microfinance has garnered significant worldwide attention as being a successful tool in poverty reduction. In 2005, the Government of India introduced significant measures in the annual budget affecting MFIs. Specifically, it mentioned that MFIs would be eligible for external commercial borrowings which would allow MFIs and private banks to do business thereby increasing the capacity of MFIs. It is clear from the previous that the objectives of the bank sector nationalization strategy have resulted into several offshoots, some of which have succeeded and some have failed. Today, Self Help Groups and Micro Finance Institutions are the two dominant form of microfinance in India. Below, the detailed description of the Self Help Group model is provided.

Model of Self Help Group

A SHG is a group of about 10 to 20 people, usually women, from a similar class and region, who come together to form savings and credit organization. They pool their financial resources to make small-interest-bearing loans to their members. This process creates an ethic that focuses on savings first. The setting of terms and conditions and accounting of the loan are done in the group by designated members. The key observations of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) about the function of SHGs can be depicted in a brief manner as follows (Kay, 2002):

- Empowerment is a process by which women take control of their lives through expansion of their choices;

- Micro credit programmes have played a valuable role in reducing vulnerability;

- Changing gender relations within the household are intrinsic to greater empowerment;

- Women’s decision making power has been enhanced by their greater economic status;

- Micro credit schemes have not been able to lift women out of abject poverty as they cannot transform social relations and the structural causes of poverty;

- With suitable support, Self Help Groups can move on to collective action at the community level but more remains to be done for sustained poverty alleviation.

In summary, the main objectives and functional issues of working of SHGs are as follows:

- empowerment of the rural people (mainly women);

- poverty eradication;

- assistance for the poorer people to take part in the market mechanism as a seller of home made goods as well as a consumer of different other goods and services;

- assistance for the poor people to increase their savings and propensity to invest through the financial assistance of different micro credit schemes.

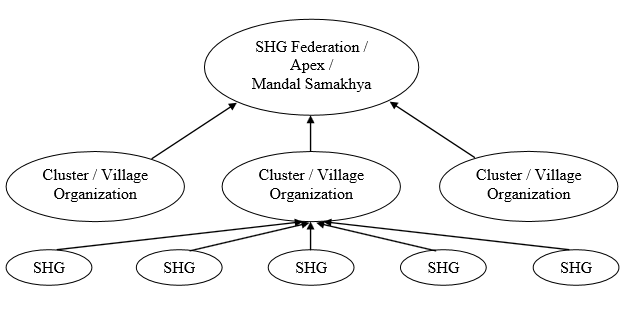

As mentioned previously, SHGs have also federated into larger organizations. In Figure 1, a graphic illustration of a SHG Federation is shown. Typically, about 15 to 50 SHGs make up a Cluster / Village Organization (VO) with either one or two representatives from each SHG. Depending on geography, several clusters or VOs come together to form an apex body or an SHG Federation. Sometimes it is called as Mandal Samakhya (federations of VOs). In Andhra Pradesh state, the Village Organizations, SHG Clusters and SHG Federations are registered under the Mutually Aided Co-operative Society (MACS) Act 1995.

Figure 1. Illustrative SHG Federation

At the cluster and federation level, there are inter-group borrowings, exchange of ideas, sharing of costs and discussion of common interests. There are typically various subcommittees that deal with a variety of issues including loan collections, accounting and social issues (Reddy and Manak, 2005). As already described, SHG Federations have presented some key benefits to SHGs as a result of their greater scale. Increasingly, SHG Federations are being seen as a key interface with the SHG movement because of their formal registration under the MACS and recognition from bankers. But, in addition to the benefits of SHG Federations, there are some drawbacks, or constraints, that should be noted. An SHG Federation is a formal group of informal common-interest groups. As a result of its rather informal members, there are internal constraints that it faces. Namely, it has a poor capacity for self-governance, average to low quality managers and systems and process are poorly defined. Further, there is significant financial cost to organizing and registering a SHG Federation which has been estimated to be about Rs. 7,000 (162.79 USD; 1USD = Rs.43) per SHG member. To bridge these internal constraints requires savvy external assistance and there are few good quality NGOs to provide this assistance to a burgeoning number of SHG Federation (Reddy and Manak, 2005).

Gender empowerment: the concept and the debates

Among the various other objectives of micro credit program the question of empowerment has been always dealt with great importance in all sorts of studies regarding the SHGs. According to the United Nations, “Empowerment is defined as the processes by which women take control and ownership of their lives through expansion of their choices” (United Nations Capital Development Fund, 2005). Thus, it is the process of acquiring the ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability has previously been denied. The core elements of empowerment have been defined as agency (the ability to define one’s goals and act upon them), awareness of gendered power structures, self-esteem and self-confidence. Empowerment can take place at a hierarchy of different levels – individual, household, community and societal – and is facilitated by providing encouraging factors (e.g., exposure to new activities, which can build capacities) and removing inhibiting factors (e.g., lack of resources and skills) (Bali, 2007). The above definition of empowerment might be elaborated highlighting mainly the choices of rural women. The expansion in the range of potential choices available to women includes three inter-related dimensions that are inseparable in determining the meaning of an indicator and hence its validity as a measure of empowerment. These dimensions are (1) Resources: The pre-condition necessary for women to be able to exercise choice; women must have access and future claims to material, human and social resources; (2) Agency: The process of decision-making, including negotiation, deception and manipulation that permit women to define their goals and act upon them; (3) Achievements: The well-being outcomes that women experience as a result of access to resources and agency. Mayoux’s (2000) definition of empowerment relates more directly with power, as “a multidimensional and interlinked process of change in power relations”. It consists of: (1) ‘Power within’, enabling women to articulate their own aspirations and strategies for change; (2) ‘Power to’, enabling women to develop the necessary skills and access the necessary resources to achieve their aspirations; (3) ‘Power with’, enabling women to examine and articulate their collective interests, to organize, to achieve them and to link with other women and men’s organizations for change; and (4) ‘Power over’, changing the underlying inequalities in power and resources that constrain women’s aspirations and their ability to achieve them. These power relations operate in different spheres of life (e.g., economic, social, political) and at different levels (e.g., individual, household, community, market, institutional). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has identified two crucial routes as imperative for empowerment. The first is social mobilization and collective agency, as poor women often lack the basic capabilities and self-confidence to counter and challenge existing disparities and barriers against them. Often, change agents are needed to catalyze social mobilization consciously. Second, the process of social mobilization needs to be accompanied and complemented by economic security. As long as the disadvantaged suffer from economic deprivation and livelihood insecurity, they will not be in a position to mobilize (UNDP, 2001). In many developing countries (especially in South Asia), one strategy which has been found to be promising is participatory institution building in the Self Help Groups, often coupled with savings and micro credit loans.

Case studies of relationship between monetary empowerment and gender empowerment

This section of the paper reveals relationship between the different concepts of empowerment through some secondary data sources. The complexities regarding the conceptual position of empowerment can be analysed through some earlier survey reports. The following case studies put some light on the level of success of SHG programs to achieve their goals mentioned earlier. Case study 1: First, the survey report of a study on Patna district of Bihar state is analyzed. This location has a strong network of NGOs and large number of SHGs. Self Help Group under Convergent Community Action (CCA) programme of UNICEF, implemented by Integrated Development Foundation (IDF) was selected for the study. This survey was organized on the basis of field surveys, group discussions among the member of the Self Help Groups. All the women interviewed were Hindus. The region is predominantly inhabited by Hindus except some population in Phulwarisharif block. The women represent different castes like Paswan, Yadav, Kurmi, Harizan, Pal, etc but class wise they are similar, considering their economic status. In life style also there is not much difference except that the other backward castes (OBCs) are better positioned socially than the Scheduled Castes (SCs). Education wise, 74 percent are illiterate, 15.5 percent are literate, 8 percent have studied up to class 5, and 2.5 percent of them have education till standard 10th. Findings from interview schedule were analyzed quantitatively and presented in Table 1. The table shows the impact of SHGs on women.

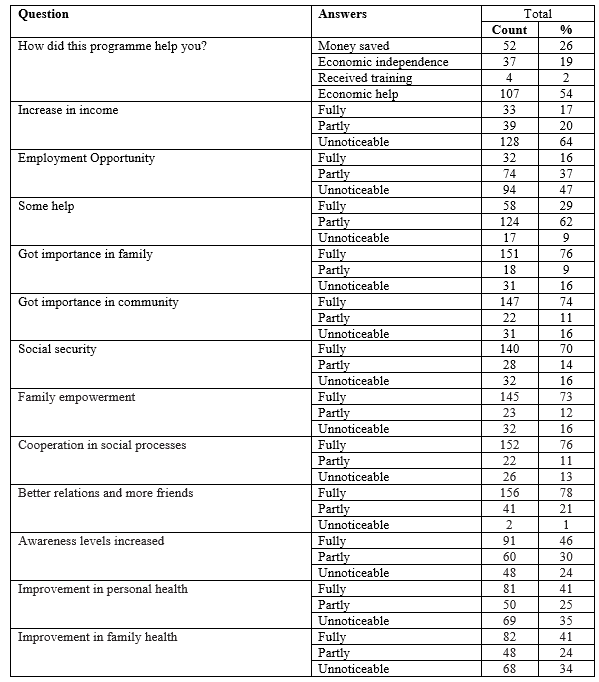

Table 1. Impact of SHG on women’s empowerment (Kumar, 2006)

From Table 1 the following findings may be defined:

- Though there is not much noticeable economic empowerment as the column ratio of economic independence is too low, the importance in family and in community has increased quite significantly.

- The microfinance program has partly helped to get an economic assistance, but lack of training is actually causing less development of skills which eventually does not help to sustain the long term fruits of initial loan advancements.

- The micro credit program has increased the social security and family empowerment.

- In the aspect of community networking and health the micro credit program has shown some impact.

These findings reveal that although Self Help Groups do not provide much economic empowerment but in the question of gender empowerment and community development the schemes may have some positive outcome which in turn can lead to a possibility of economic development if the members get proper skill and knowledge assistance from the respective NGO and government bodies.

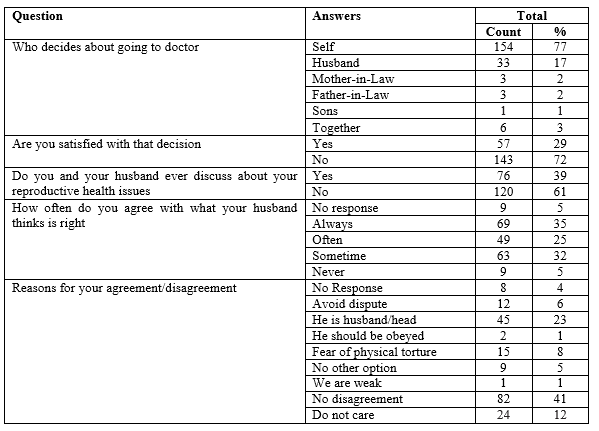

Table 2. Impact of SHG on Empowerment and Health (Kumar, 2006)

As it can be seen from Table 2, the Self Help Group project has some positive impact in terms of household decision making in the aspect of taking care of individual health as the column percentage is significantly high (77%). But in the next question the satisfaction with the decision shows quite a large number of disagreements, which is certainly not an expected response. This disagreement can arise from various reasons such as economical, cultural and sociological factors. This can be further elaborated with the answer to next question regarding the discussion of reproductive health issues. The large percentage of “no” answers may be attributed to various other social and cultural factors, and it may not give proper indication of women’s decision making power after joining the SHG programme. This may be explained by the fact that in many rural areas in India this sort of discussions is almost traditionally forbidden due to many types of conservativeness regarding sexual issues. It may not have relation with the question whether a rural woman gathered confidence to take her decision regarding her health issue or not. However it is difficult to compare the situation before and after the participation in the Self Help Group due to limited information regarding the situation before joining the programme. Table 2 actually shows that in the sample of study most women can take their decision regarding their health issues. This helps to understand to what extend the decision making power is gained by the rural women in this sample of study. Nevertheless, due to the lack of information, it cannot be clearly analysed, whether or to what extent the situation has improved. The contradictory response may encourage researchers to analyze this matter more deeply.

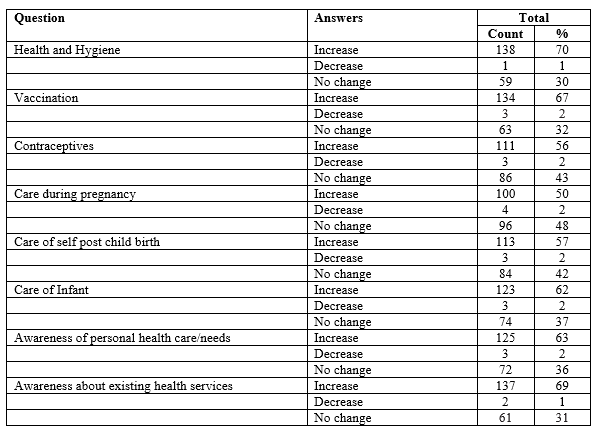

Table 3. Impact of SHG on Health knowledge and Awareness (Kumar, 2006)

Table 3. Impact of SHG on Health knowledge and Awareness (Kumar, 2006)

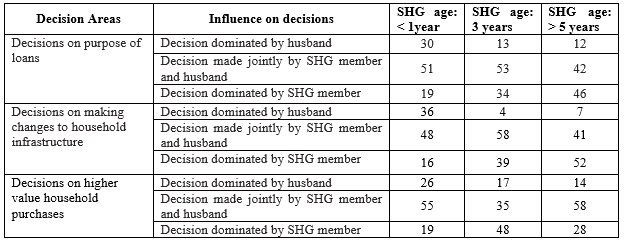

From Table 3 it is evident that this SHG schemes have created a fruitful impact in the context of health awareness, as vaccination, use of contraceptives, care during pregnancy, care of infant etc. have all showed a positive increasing trend. Thus, it can be assumed that monetary empowerment leads to gender empowerment. Case study 2: This is a case study under the programmes Swashakti, Stree Shakti, Sujala and Kawad implemented to promote the number of SHGs in the southern state of Karnataka. These programmes are carried out in several districts of Karnataka to achieve empowerment of rural people through greater participation in Self Help Groups. In the year 2004, NABARD conducted surveys on several Self Help Groups of Karnataka to get an overview of impact of Self Help Groups in the lives of rural people, say whether it is, increment in savings rate and bank linkages or increment in the power of decision making. Table 4 analyzes increase of the power of decision making of women SGH members.

Table 4. Increased decision-making power of women SHG members in their households, per cent (Government of Karnataka Department of Planning & Statistics, 2005)

Table 4. Increased decision-making power of women SHG members in their households, per cent (Government of Karnataka Department of Planning & Statistics, 2005)

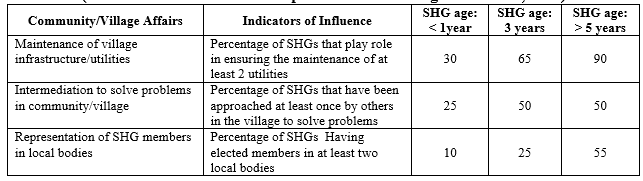

Table 5 provides data on increase of SHGs’ influence over the community.

From the results of surveys conducted in Karnataka, it can be said that in this case participation in SHGs mattered as it has enhanced the power of decision making. Moreover as the group grew older the members acquired more power in both the household as well as in the community level. So as the time goes the decision making power of women has increased and the influence of male member (mainly husband) in the decision making has decreased. This is clear from table 4 as the number of women taking decision in SHG’s of 3 years old has increased in the percentage terms as the group grow older and reaches 5 years. So this case study reflects the time effect on these schemes. It can be inferred that the role of time is very important to get any significant impact of the Self Help Groups as the adoptive capabilities of group members depend on several other factors and this process is very complex indeed. Thus, positive relationship between monetary empowerment and empowerment of the rural women is revealed by these figures. There are some other case studies also from states of Orissa, Tamilnadu and Andhrapradesh, where SHGs carry out the following empowerment building activities: sending children (both girls and boys) to school more regularly; improved nutrition in the household; taking better care of health and hygiene of the children; taking care of other group members in time of health and psychological crisis. This includes, for instance, taking a pregnant member within their group to a hospital for delivery of a child, helping a group member with household and incomegenerating activities at the time of loss of her husband (Chiranjeevulu, 2003). In these areas micro credit institutions have helped the rural women to get control over their decisions. But still lack of knowledge about their rights and lack of awareness of their position in the family as well as in the community is creating barriers in the path of their self reliance and empowerment. In some cases it appears that women in rural in India are now taking decisions which are traditionally considered as outside the domain of women, such as: overcoming the resistance from husband and other members of the family to join the SHG, participation in decision-making within the household to issues that were usually considered outside the domain of women, Programmes, adopting family planning measures, eradication of prostitution etc. (Usha, 2003). Thus, the analysis of the second case confirms that monetary empowerment leads to gender empowerment. These case studies are supported by the quantitative values and relying on that many researchers have proposed various models, but the models are not unambiguous and also the quantitative values are not easy to interpret. There are many cases in which increase in the monetary freedom and decision making of women lead to domestic violence as the male members do not always welcome the changes. Thus, even if there are empowering activities the sole power of taking decisions in household level still remained in the hands of the male members. In the next section, a model is formulated for getting a closer quantitative look to this issue.

From the results of surveys conducted in Karnataka, it can be said that in this case participation in SHGs mattered as it has enhanced the power of decision making. Moreover as the group grew older the members acquired more power in both the household as well as in the community level. So as the time goes the decision making power of women has increased and the influence of male member (mainly husband) in the decision making has decreased. This is clear from table 4 as the number of women taking decision in SHG’s of 3 years old has increased in the percentage terms as the group grow older and reaches 5 years. So this case study reflects the time effect on these schemes. It can be inferred that the role of time is very important to get any significant impact of the Self Help Groups as the adoptive capabilities of group members depend on several other factors and this process is very complex indeed. Thus, positive relationship between monetary empowerment and empowerment of the rural women is revealed by these figures. There are some other case studies also from states of Orissa, Tamilnadu and Andhrapradesh, where SHGs carry out the following empowerment building activities: sending children (both girls and boys) to school more regularly; improved nutrition in the household; taking better care of health and hygiene of the children; taking care of other group members in time of health and psychological crisis. This includes, for instance, taking a pregnant member within their group to a hospital for delivery of a child, helping a group member with household and incomegenerating activities at the time of loss of her husband (Chiranjeevulu, 2003). In these areas micro credit institutions have helped the rural women to get control over their decisions. But still lack of knowledge about their rights and lack of awareness of their position in the family as well as in the community is creating barriers in the path of their self reliance and empowerment. In some cases it appears that women in rural in India are now taking decisions which are traditionally considered as outside the domain of women, such as: overcoming the resistance from husband and other members of the family to join the SHG, participation in decision-making within the household to issues that were usually considered outside the domain of women, Programmes, adopting family planning measures, eradication of prostitution etc. (Usha, 2003). Thus, the analysis of the second case confirms that monetary empowerment leads to gender empowerment. These case studies are supported by the quantitative values and relying on that many researchers have proposed various models, but the models are not unambiguous and also the quantitative values are not easy to interpret. There are many cases in which increase in the monetary freedom and decision making of women lead to domestic violence as the male members do not always welcome the changes. Thus, even if there are empowering activities the sole power of taking decisions in household level still remained in the hands of the male members. In the next section, a model is formulated for getting a closer quantitative look to this issue.

A proposed model to estimate the influence of SHGs on women’s empowerment: its problems and possibilities

Many researchers in India has already attempted to build a regression model estimating the panel data with the help of probit model and taking ordinal variables in some probability distribution function (Pitt et al., 2006). But all these models have some problems regarding the suitable indicators of empowerment. Ackerly (1995) constructs an indicator, Accounting Knowledge, to measure the probability that the changes associated with empowerment intervene. In this paper, a regression model is offered, which assigns empowerment levels certain scores and treats this as explained variable, meanwhile taking money income, years of participation, education levels as explanatory variable. Qualitative variables as dummy variables incorporated in this model are as follows:

1.whether beaten by husband after joining SHGs :

D1=1 if yes

=0 otherwise

2.whether takes the decision what items to cook after joining the SHGs:

D2=1 if yes

=0 otherwise

3.whether takes the decision to purchase jewellery or other major household items after joining SHGs:

D3=1 if yes

=0 otherwise

4.whether go and stay with her parents or sibling after joining the group:

D4=1 if yes

=0 otherwise

5.whether takes the decision how to use the money she earns :

D5=1 if ye

s=0 otherwise

With the help of the listed dummy variables, models may be constructed for investigating the influence of MFIs on the empowerment of women. But the problem with the data set will always persists as the response of the respondents depends on lots of other social and cultural forces. It depends on the outlook of the respondent towards the social reality. Even the collection of this response sometimes becomes very problematic. But this proposed model with suitable dummy variables can be used in regression analysis. The main problem in modelling empowerment is to tackle the qualitative variables. So the model with the above dummies can give some light in the consequence of life of a woman before and after joining a Self Help Group. This model is an attempt to analyze the empowerment in terms of some qualitative variables captured by dummies and if the primary data is available then it may indicate the variables that play significant role to achieve empowerment in individual level.

Microfinance and women’s empowerment

In India, a majority of microfinance programmes target women with the explicit goal of empowering them. There are varying underlying motivations for pursuing women’s empowerment. Some argue that women are amongst the poorest and the most vulnerable of the underprivileged and thus helping them should be a priority. Whereas, other believe that investing in women’s capabilities empowers them to make choices which is a valuable goal in itself but it also contributes to greater economic growth and development. It has been well-documented that an increase in women’s resources results in the well-being of the family, especially children (Mayoux, 1997; Kabeer, 1999; Hulme and Mosley, 1996). A more feminist point of view stresses that an increased access to financial services represent an opening/opportunity for greater empowerment. Such organizations explicitly perceive microfinance as a tool in the fight for the women’s rights and independence. Finally, keeping up with the objective of financial viability, an increasing number of MFIs prefer women members as they believe that they are better and more reliable borrowers. Hashemi et.al (1996) investigated whether women’s access to credit has any impact on their lives, irrespective of who had the managerial control. Their results suggest that women’s access to credit contributes significantly to the magnitude of the economic contributions reported by women, to the likelihood of an increase in asset holdings in their own names, to an increase in their exercise of purchasing power, and in their political and legal awareness as well as in composite empowerment index. They also found that access to credit was also associated with higher levels of mobility, political participation and involvement in “major decision-making” for particular credit organizations. Holvoet (2005) finds that in direct bank-borrower minimal credit, women do not gain much in terms of decision-making patterns. However, when loans are channelled through women’s groups and when they are combined with more investment in social intermediation, substantial shifts in decision-making patterns are observed. This involves a remarkable shift in norm-following and male decision making to more bargaining and sole female decision-making. She finds that the effects are even more striking when women have been members of a group for a longer period and especially when greater emphasis has been laid on genuine social intermediation. Social group intermediation had further gradually transformed groups into actors of local institutional change. Mayoux (1997) argues that the impact of microfinance programmes on women is not always positive. Women that have set up enterprises benefit not only from small increases in income at the cost of heavier workloads and repayment pressures. Sometimes their loans are used by men in the family to set up enterprises, or sometimes women end up being employed as unpaid family workers with little benefit. She further points that in some cases women’s increased autonomy has been temporary and has led to the withdrawal of male support. It has also been observed that small increases in women’s income are also leading to a decrease in male contribution to certain types of household expenditure. Rahman (1999) using anthropological approach with indepth interviews, participant observations, case studies and a household survey in a village, finds that between 40% and 70% of the loans disbursed to the women are used by the spouse and that the tensions within the household increases (domestic violence). Mayoux (1997) further discusses that the impact within a programme also varies from woman to woman. These differences arise due to the difference in productive activities or different backgrounds. Sometimes, programmes mainly benefit the women who are already better off, whereas the poor women are either neglected by the programmes or are least able to benefit because of their low resource base, lack of skills and market contacts. However, poorer women can also be more free and motivated to use credit for production. Mayoux (2001) also warns about the inherent dangers in using social capital to cut costs in the context of other policies for financial sustainability. The reliance on peer pressure rather than individual incentives and penalties may create disincentives and corruption within groups. Reliance on social capital of women clients along with increasing emphasis on ideals on strict economic accounting at the programme level require increased voluntary contribution by the members in terms of time and effort. It has been noted that those putting in voluntary contributions also expect to be repaid in the form of leadership of the group. Another issue that needs further investigation is whether without change in the macro environment, microfinance reinforces women’s traditional roles instead of promoting gender equality? A woman’s practical needs are closely linked to the traditional gender roles, responsibilities, and social structures, which contribute to a tension between meeting women’s practical needs in the short-term and promoting long-term strategic change. By helping women meet their practical needs and increase in their efficacy in their traditional roles, microfinance can help women to gain respect and achieve more in their traditional roles, which in turn can lead to increased esteem and self-confidence. Although increased esteem does not automatically lead to empowerment it does contribute decisively to women’s ability and willingness to challenge the social injustices and discriminatory systems that they face (Cheston and Kuhn, 2002). Finally, it is important to realize that empowerment is a process. For a positive impact on the women’s empowerment may take time.

Conclusions

In conclusion, relationship between MFIs and the gender empowerment is not very transparent in most of the cases. Furthermore any one-to-one correspondence is hardly been seen in most of the cases. Any strong conclusion about the relationship between these two might lead to problem of oversimplification and eventually wrong understanding of the issue. Actually a multidisciplinary approach to this issue is necessary. Economic factors have to play a major role in the question of gender empowerment but religious, sociological and anthropological factors has to be included in this genre of institutional economics to study the role of MFIs in a more comprehensive way. Even the role of macro variables has to be simultaneously checked for the better understanding of the group performance in micro level. Analysis of researches performed by other authors and institutions, allows indicating a positive relationship between the MFIs and gender empowerment, but still there are many scopes for further research. So the impact of Self Help Groups as institutions of women’s empowerment is still an open ended question of research. Therefore, further sophisticated estimation methods and models should to be applied to get a more concrete view in this complex issue. Above all, the notion empowerment still needs some further conceptual elaborations and its definition is still a debatable issue among the leading researches around the world.

References

- Ackerly B.A. (1995) Testing the tools of development: credit programmes, loan involvement and women’s empowerment. Getting Institutions Right for Women in Development, IDS Bulletin, Vol. 26, No. 3.

- Bali S. R. (2007) Can Microfinance Empower Women? Self-Help Groups in India. Dialogue, No. 37, ADA, Luxembourg.

- Cheston S., Kuhn L. (2002) Empowering Women through Microfinance: draft. Opportunity International.

- Chiranjeevulu T. (2003) Empowering Women Through Self Help Groups – Experiences in Experiment”, Kurukshetra, March.

- Government of Karnataka Department of Planning & Statistics (2005) Self-Help Groups: Empowerment Through Participation. Karnataka Human Development Report, available at: http://planning.kar.nic.in/khdr2005/English/Main%20Report/14-chapter.pdf.

- Hashemi S.M., Schuler S.R., Riley A.P. (1996) Rural Credit Programmes and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 635-653.

- Holvoet N. (2005) The Impact of Microfinance on Decision-Making Agency: Evidence from South India. Development and Change, Vol. 36, No. 1.

- Hulme D., Mosley, P. (1996). Finance against poverty, Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Kabeer N. (1999) Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change, Vol. 30, pp. 435-464.

- Kay T. (2002) Empowering women through self-help microcredit programmes. Bulletin on Asia-Pacific Perspectives 2002/03, available at: http://www.unescap.org/drpad/publication/bulletin%202002/ch6.pdf.

- Kumar A. (2006) Self-Help Groups, women’s health and empowerment: global thinking and contextual issues. Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies XISS, Ranchi, Vol. 4, No. 3, September 2006, pp. 2061-2079.

- Mayoux L. (1997) The Magic Ingredient? Microfinance and Women’s Empowerment. A Briefing Paper prepared for the Micro Credit Summit, Washington, February.

- Mayoux L. (2000) Microfinance and the empowerment of women: A review of the key issues. Social Finance Unit Working Paper, 23, ILO, Geneva.

- Mayoux L (2001) Tackling the Down Side: Social Capital, Women’s Empowerment and Micro-Finance in Cameroon. Development and Change, Vol. 32.

- MYRADA (2002) Impact of Self Help Groups (Group Processes) on the Social Empowerment Status of Women Members in Southern India, paper presented at the Seminar on SHG Bank Linkage Programme, New Delhi.

- NABARD (2004) SHG-Bank Linkage programme in Karnataka, pp. 117-118, pp. 127-128.

- NABARD (2005) Progress of SHG – Bank Linkage in India, 2004-2005, Microcredit Innovations Department, NABARD, Mumbai.

- Pitt M., Khandker S. R., Cartwright J. (2006) Empowering Women with MicroFinance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change, pp. 791- 831

- Rahman A. (1999) Microcredit initiatives for equitable and sustainable development: who pays? World Development, Vol. 27, No. 1.

- Reddy C. S., Manak S. (2005) Self-Help Groups: A Keystone of Microfinance in India – Women empowerment & social security. Mahila Abhivruddhi Society, Andhra Pradesh (APMAS), available at: http://www.empowerpoor.org/downloads/SHGs-keystone-paper.pdf.

- Singh K. (2005) Banking Sector Liberalization in India: Some Distributing Trends. ASED, August 29, 2005.

- UNDP (2001) Newsfront. Global Microfinance Meeting Charts New Directions, available at: www.undp.org/dpa/frontpagearchive/2001/june/1june01/

- United Nations Capital Development Fund (2005) Building Inclusive Financial Sectors to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals: concept paper.

- Usha K. (2003) Gender , Equality and Development. Yojana.

- Yunus M. (2004) Grameen Bank, Microcredit and Millennium Development Goals. EPW Special Articles, September 4.