Ţuclea C. E., Ţigu G., Popescu D. (2008). The economic, legislative and social characteristics of sustainable development in Bucharest metropolitan area. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 1, No. 5, pp. 26-43. ISSN 2029-0365. [www.ScholarArticles.net]

Authors:

dr. Claudia- Elena Ţuclea, Academy of Economic Studies, Romania

Gabriela Ţigu, PhD. Academy of Economic Studies, Romania

Delia Popescu, PhD. Academy of Economic Studies, Romania

Abstract

Bucharest has significantly evolved from a small village to the metropolitan area it is today. Is Bucharest ready to assume its role as a metropolis? Which are the economic and social developmental aspects of the previously mentioned area? Is Bucharest able to develop itself as a metropolis in a sustainable way? These are a few questions to be answered in our study, being given the novelty and importance of this matter in Romania. Bucharest experienced an urban expansion in the 20th century when it was recorded a spectacular increase in population (about 2 000 000 nowadays). The first step of the urbanization process is related to the migration of rural population toward the industrial centre, creating a process of growth and urban concentration. After 1990, Bucharest’s urbanization process enters its second phase, suburbanization, process which essentially reflects the “ex-urbanization” trend. We are now witnessing at a spontaneous development of the metropolitan area. This type of growth needs a very well designed intervention to correct the potential negative effects and to optimize the process, aiming a better quality of life for inhabitants.

Introductory workcase about the metropolitan areas

Most of the metropolitan areas are defined in some social and urbanity studies as locations situated into or outside the metropolitan area function with economic, social, urbanity and administrative reasons, so that area development had the optimum conditions, such as the regions of Paris, Rome, Porto, Madrid, Budapest, etc. Hall and Hay (1980) revealed the changes that occurred in the Western and Central European urban systems and drew a parallel between Eastern Europe and Japan. Within the European Union, there is a growing concern regarding the development of the European community as metropolitan areas or functional urban regions. Since 1999, EU states have approved a “Schedule of Development of the European Community” (SDEC) that refers to an integrated development strategy of the metropolitan areas from “the Grande Europe”. A first document regarding such an approach is “The Metropolitan Magna Charta: Statement from Porto on the Strategy about Issues as Planning and Regional and Metropolitan Areas Development in Europe”. In Europe, there are 120 regions or big metropolitan areas and many of these are already members of the European Network of Regions and Metropolitan Areas (METREX), established at the Metropolitan Regions Conference, Glasgow, 1996. These regions have a population of over 500 000 inhabitants that have many common challenges and opportunities. This common agenda represents the basis of collaboration and information exchange within METREX and also the big value given by the participation to this association (METREX, 2004-2005). Therefore, building a metropolitan area around Bucharest is an interesting issue not only for the Romanian community but also for the European one. Academic and practical concerns about the metropolitan areas refer to lot of issues all over the world. The first issue refers to the extension of the urban areas, which is seen as a result of the action of three powerful forces: increase in number of population, increase in income and decrease of transportation costs (Brueckner, 2000). Urban extension and creation of metropolitan areas set up a big concern: sustainable development of this space. The first requirement refers to planning and managing the new built areas in order to develop a strategic management. Environment issues refer to the usage of water, energy, solid dump goods, land and conservation preserving areas, according – Franzi et al. (2006), Bautista and Pereira (2006). The creation of metropolitan areas also implies making decisions about the population and managing the space created as new patterns of production and residency appear, according to Arias and Borja (2007). Gao and Asami (2007) identify another consequence of the development of metropolitan areas: the need of evaluating the urban space and of revealing the economic value of the facilities in this space. Data regarding the towns of Tokyo and Kitakyushu suggested that, in either city, the compatibility of the buildings and the greenery of the neighbourhood were distinctively perceived; these factors significantly influenced land prices, and the marginal effects were similar for both cities. Same idea is revealed in Prato’s (2001) publication as well. The problems regarding public transportation in metropolitan areas represent a concern for many areas in the world. Heyns and Schoeman (2006) show that, despite the best efforts of transport planners and economists, the measures have unwanted effects on the urban environment in which we live. The creation, organization and management of Bucharest Metropolitan Area face all the above-mentioned issues.

Metropolitan Area of Bucharest

The city of Bucharest has a long and interesting history. It passed through the very different epochs, from a green village to a desired metropolis status. On its path, there were some important moments, all of them being convergent to the nowadays effort to design a metropolitan area labelled MAB (Metropolitan Area of Bucharest).

Definition of the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest

Short history of Bucharest. Founded in 1459, Bucharest became the capital of Romania in 1649. The development of the city was due to the trade activities, to its geographic position that conferred the statute of an important commercial knot in the south of Romania but also in the southeast of Europe. Until the 18th century, the Bucharest had a rural aspect, being a huge village dissipated between gardens, with serpentine streets and bridges, unaligned houses, and only religious edifices being pointed out by their greatness. After 1810, influences from the West appear, and the eastern customs lose their importance (Gherasim, 2005). On the second half of the 19th century, Bucharest resembles a European capital by its architecture, gardens, social and cultural life, inspired by the Paris fashion, but especially by the implemented elements of novelty. That was the period when Bucharest was called “the little Paris”. In 1859 Bucharest becomes the first gas-lighted town worldwide (the towns in the West Europe introduced public lightning only 2 years later), and since 1861 Bucharest is the first town that introduces gas lamps, before Paris and Berlin. The most prosperous period of the town subsisted until the beginning of the Second World War. After 1945 started a period of total changes, on many levels, under the communist administration. The prosperous age of Bucharest collapsed; French, which could be heard on the streets and in the saloons of the Little Paris, was replaced with Russian, and the whole Romania was insulated from the Western world. The communist period had a strong negative impact on the architectural patrimony of Bucharest with all new buildings and urbanity sketches suffering from the Soviet influence (Gherasim, 2005). Buildings with a strong Soviet influence were built: the Spark House and the huge People’s House, symbol of the greatness mania of the dictator Ceausescu, which triggered many architectural controversies because it was perceived as ugly and useless by the Romanians, but admired and considered as postmodern by the westerners. This new administrative centre was build between 1984-1989, and in order to make room for it, over 40 000 buildings, houses and administrative edifices, priceless art, and cultural monuments, churches were demolished. Nearby the People’s House were built large avenues and towering buildings that nowadays accommodate ministries and different institutions. The subversion of communism produced a new change in Bucharest’s life, the city trying to bridge the gap with the West, but the urban harmony and the aesthetic quality of many buildings do not correspond to the claims of a big European city. As a result of the spontaneous evolution of the city and its metropolitan area, there was raised the issue of scientific determination of this area, which would allow the best administration. In Romania, the urbanisation process determined the emergence, as well as in other countries, of some poles of urban development. Obviously, the city of Bucharest, being the biggest and with function of capital has the most diverse experience of all (CURS, 2003). The methodology of determining the metropolitan area of Bucharest. Having accepted the idea and reality that metropolitan areas are formed from a pole city (or more, if they are spatially boned) and the locations from its surroundings, strongly connected to it, then the essential issue is determining the borders and the locations that are part of the same area. There are many methodologies of determining the locations of a metropolitan area, starting with the easiest, that of establishing the maximum distance from the centre of the city, and ending with the most complex one, when the borders are established by applying a methodology of evaluating the relationship between the central city and its outside area (this area is differently called: periurban, preurban, extra urban, commuting, pre-metropolitan, etc.). Among the most used criteria for determining the borders of metropolitan areas, besides the distance towards the city (often calculated as the duration of moving with the most frequently used transportation means by people in the surrounding cities), are: percentage of individuals from localities who come daily to work in the metropolis (in USA, this percentage is 15%), percentage of the people from localities involved in non-agricultural activities related to the city (at least 75% from the employed people to work in non-agricultural activities), percentage of people employed in agricultural activities for the city, percentage of people with residence in the city, localities’ touristic potential, etc. (CURS, 2003). A well known experience and closer to the Romanian reality is the European Center of Coordination and Research in Social Science from Vienna, which elaborated between 1972 and 1973 the pattern of determining the Functional Urban Region in the form of SMLA (Standard Metropolitan Labour Area) and MELA (Metropolitan Economic Labour Area). SMLA includes the territory towards which over 15% from the active economic residents go daily to the metropolis, and MELA includes the territory with people that go daily for working in the central town.

Where: Ii= the length of commute in area i

Cij= the commute level between area i and area j

REAi= active economic residents (employees) in area i

In Romania, the studies published by Abraham (1991) in “Introduction to Urban Sociology” are also known. This research was done in collaboration with sociologists, geographers and economists to determine the periurban area of Bucharest. There were taken into consideration indicators concerning the following dimensions: labour force, city supply with perishable goods, touristic potential, distance and spatial continuity with the pole city.

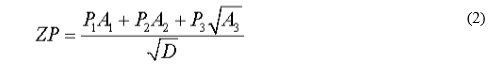

Where:

P1, P2, P3 = percentage for the three indicators

A1, A2, A3 = standard values for the three indicators (labour force, agriculture for the city and touristic potential)

D = distance towards Bucharest

By applying this formula to settlements within a distance up to 50 km around Bucharest, a periurban area was obtained that contained 77 villages, from which 22 represented the immediate periurban, 36 the close periurban and 19 the distant periurban area. Along with the city of Bucharest, these villages from the periurban area represented the regional function of the city. In this study, the above experiences are adapted and updated to the new realities, and the borders of the metropolitan area of Bucharest are scientifically determined. According to other newest methodology, the metropolitan area of Bucharest would contain a smaller number of localities as function of some indicators, as in the formula:

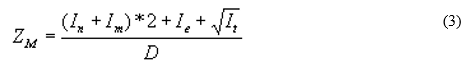

Where:

- In = commute index

- Im = migration index

- Ie = town renewal index

- It = touristic potential index

- D = distance in time towards Bucharest

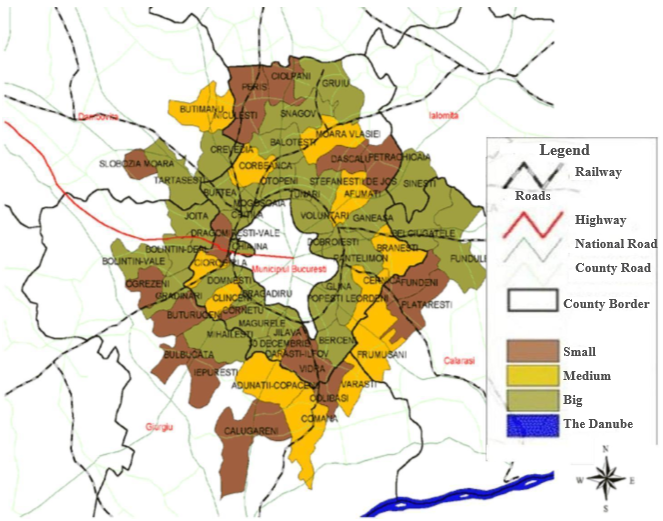

Multiplication of (In+Im) by 2 indicates that the commute and the migration are in a double relation: towards the city and from the city towards the locality in the influence area. Drawing out the radical from It shows that it represents more a potential than an effective relation. Therefore, the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest (MAB) would be formed of the city of Bucharest + 62 settlements in its influence area (see Figure 1). However, an important factor for including the localities in the MAB is the approval of the respective communities for being included in the metropolitan area.

Figure 1. The Metropolitan Area of Bucharest

Whatever future structure the metropolitan area would have, it must represent the interests of all the associated communities, regardless their sizes or geographic positions. This will happen only if the decision factors at local level (mayors, local commissioners etc.) identify the priorities of their communities and then collaborate in a coherent and organised way with the other future partners in order to establish together the best organisational form of metropolitan area.

Economic aspects of the development of the MAB The politic, social, and economic life between the city and the surrounding region has always been connected. According to Barnes and Ledebur (1993), the symbiotic relation between the compact city and the localities with low demographic density is reflected by how the economic and political future of the suburban areas influences the economic and political success of the city. The dominant economic function such as preferred location for large corporations, research and development centres, harbours, and logistics knots directly leads to sustainable development strategies. Moreover, strategic reports demonstrated that a region’s geographic position at a European scale answers to specific development priorities (METREX, 2004-2005): the regions of the Central and Eastern Europe have the role of managing the national economic restructuring processes; the regions try to capitalize on the sustainable regional development; for the regions of the Northern and Western Europe a key problem is the management of conflicts generated by the need of using the territory; the metropolitan regions in the Mediterranean Sea area try a better integration in the welfare of European key regions. As part of the globalisation of economic activities, the further extension of the European Union represents the most powerful external factor that establishes the pace of changes occurring in metropolitan areas. Regions of the Central and Eastern Europe deal with opportunities and difficulties revealed in the transition period started in the 90’s. For example, the Moscow region (the most populated metropolitan region of Europe) earns a high profile as favourite location of the international companies in the central and east European market, while cities as Budapest, Prague or Warsaw compete for getting international functions in selected areas (finance, communication, research, education) and for those functions as access portal for investors from other parts of the world (CURS, 2003). Core-cities of the metropolitan areas of the regions of the Central and Eastern European countries became both the central points of social disequilibrium and the favourite target of national and international migrations. Metropolitan areas from Central and Eastern Europe must discard a part of the economic and social pressures to the nucleus city. The economic dynamic and regional relocation entails also risks for the urban and natural environment. The development of the EU structures affected a large part of the metropolitan regions all over Europe. New trans-European connections and great speed railways are now developing, and thus the majority of the metropolitan regions aim to become either a part of a connection track of European markets (for the regions from the Europe periphery) or nodal points in the future system of European infrastructure. The metropolitan regions from the border of the old “Iron curtain” have started to exploit the advantages of their geographical position. For instance, Vienna (localized at the intersection of 3 big axes of the Trans-European Network (TEN)), Budapest (localized at the intersection of 5 axes), and Berlin/Brandenburg are good examples of a developed system of merchandise distribution. The importance given to the integration of metropolitan regions into an international transportation network is revealed by the recent developments of airports (ESPON Project, 20022004). Almost every representative metropolitan region in Europe invests a lot in airport facilities, which is considered an indispensable factor for the international functions. Besides the problems brought by the integration of isolated parts of Europe, such as the ones from the Central and Eastern Europe, the creation of a European Market, as part in the globalization process, had a great impact on the metropolitan regions development. Regions that used to have an economy based on manufacturing, like the metropolitan area of Bucharest, must now move on towards an economy based on knowledge, with a well developed sector of services. The problems of regions in the reorganization process could be solved by the reinforcement of the private sector that could lead to an easier process of economic adaptation. Assuming the European model, the MAB should consider the sustainable regional development by targeting the following main objectives:

- balancing the metropolitan spatial structure;

- improving the life quality at urban level;

- keeping the regional identity, by capitalizing on the cultural patrimony;

- integrating management through the cooperation of regional infrastructure networks;

- creating new planning and implementation partnerships.

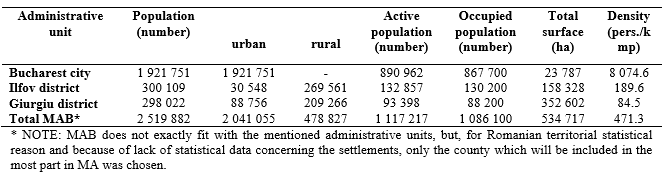

The dynamic of forming and developing the MAB is strongly marked and determined by the city’s capacity to put together all energies from the public, the private sectors and the civil society into a perspective strategic project. The consensus of all players and the emergence of a metropolitan power represent the basic conditions for applying a metropolising strategy (this is the case of the cities of Manchester, Lisbon, Madrid and many others (METREX, 2005)). The coordination of economic and social policies on territories containing administrative borders of several localities requires new models of management and new planning instruments. In a competitive landscape, it is not enough to put together all the resources of the local administration.Social aspects of the MAB development The main challenges that the development of the metropolitan areas must face are the demographic problems. External and internal migratory features of the metropolitan areas represent a main factor to be taken into consideration, especially due to the migration from the nucleus city towards suburbs and surroundings. Moreover, the aging of population means a decrease of the birth rate, the longevity, and the improvement of life quality, all of these acting on the increase of pressure on social services (education, medical services, and habitation). For Bucharest, the main source of development was the rural-urban immigration, mainly of the population from the rural areas to the industrial town that was in process of creating jobs, starting with the second half of the 19th century. This was the context that the city of Bucharest developed from 65 000 inhabitants in 1831 to 770 000 in 1930 and 1 120 000 in 1948, to over 2 000 000 in 1989 (nowadays being 1 921 751; out of this number, 891 000 represent employed population with an unemployment rate of 2.6%) (Romanian Statistical Yearbook, 2006; Institutul Naţional de Statistică, 1998-2008), continuing what is called the first stage of the urbanism process, stage where the rural population is prone to migrate towards the urban centre, thus determining a process of urban growth and concentration (see Table 1). Data of Table 1 are interpreted by the authors basing on official statistics in Romania.

Table 1. Demographic Indicators of MAB in 2006

Obviously that the urban expansion through attracting the labour force, mostly from the rural areas, was associated both with industrial integration processes (the majority of the labour force was made of villagers or young people from rural areas who needed a process of integration into the urban industrial activity) and the process of a locative infrastructure development. The latter, as a rule, got the form of some districts of residences made up of houses with relatively standard apartments, the so called “bedroom districts”, that hold a great part of the population. In Bucharest over 40% of inhabitants were residents or beneficiaries of such a residence. Concurrently with the urban attraction exerted by the city through immigration from the rural areas, the city attracted also a part of the labour force from its surroundings which continued to keep its residence to the rural areas but went daily for working in town, forming what the sociologists call the category of workers-villagers (or villagers-workers). Such a population was not urban or rural, had a dual way of life of workers and villagers, mostly combining the two types of activities. The percentage of this workers-villagers category sometimes reached 20% from the city’s employed population, and that made the commute to be considered in the ex-socialist countries as a particular phenomenon, as a transition from rural towards urban that was specific for a “partial urbanisation” when aspects of rural way of living combined with the ones of using the work and trade services (although the cultural-sportive aspects were not excluded) of the city. Nowadays, the daily flow of commuters towards Bucharest is over 480 000 persons (ALMA-RO Association, 2006b). This way, the connections between the city and its preponderant rural hyper land have become closer. The connections between people from the surrounding localities and Bucharest have become permanent and more diverse. After 1990, the urbanisation process for the city of Bucharest started to move to the second stage namely the suburbanisation, process that reveals the tendency of “exurbation” or residential mobility of citizens from the centre towards periphery or exterior area. A significant proportion of citizens, mainly those who succeeded to earn larger incomes, started to build their own houses in the surrounding areas of the city (holiday houses or permanent residences) generating a development of the existing localities or creating new areas of living by overwhelming investments of the private sector. Urbanisation at this level starts to confirm the stages that this process followed in the developed countries, the stage of suburbanisation being obviously a tendency not only for the buildings that have begun to populate the surrounding territory, but also for the buildings of services mainly malls or hypermarkets and stores located on the main communication paths. These all reveal the fact that the development of the city of Bucharest and of its surroundings is certainly a tendency of organic spontaneous development of a metropolitan area. Such an evolution needs an appropriate arrangement, legislative, scientific and management interventions, that should correct the possible negative effects and optimize the process and thus lead to the improvement of the quality of lives of inhabitants in such an area.

Legal aspects of the MAB development

In Romania, problems that follow the decentralization process of the administrative structure under a centralized government, such as increasing differences between urban/rural areas and new ambitions of big cities trigger difficulties that exceed the managing capacity of the currently fragmented administration. Therefore, they try to create new management forms which include territories that are under the jurisdiction of different local councils, with different interests and development priorities. This is why, Law No. 351/2001, regarding the approval of the National Territory Arrangement Plan, the 4th section, The Localities Network, opens up the public-private partnership on strategic programmes of urban and/or rural territory development through the metropolitan areas definition. “Area formed by association, on voluntary partnership bases, between the big urban centres (the capital of Romania and the first grade towns) and urban and rural localities in the closed area, at distances up to 30 km, that developed between them cooperation relations on multiple levels” (Law No. 351/2001, annex 1, pct. 11). It specifies the functioning way of the metropolitan areas: “The metropolitan area (….) works as independent entities without legal personality” (Law No. 351/2001, art. 7, par. 2). However, the law does not foresee forms of managing the metropolitan plan, forms of monitoring and controlling the area metropolitan development. Local councils separately could accomplish a plan of metropolitan territory arrangement, but they deal afterwards with problems appeared in the implementation stage of the plan. These problems are related to territorial, economic and environmental coordination generated by the interaction of economic flow both inside the metropolitan area and between it and the national and international economy. Legislation is focused on more legal aspects of collaboration and less on political and economical aspects of it. Meantime, the Territory Arrangement and Urbanism Law No.350/2001 foresee that the metropolitan territory is “the surface situated around big urban congestions, established through speciality studies, within there are created mutual relationships of influence in the communication paths, economic, social, cultural and town infrastructure domains” (Law No. 351/2001, annex 2). Moreover, the Zonal Territory Arrangement Plan, defined in this law, can easily be adapted to the harmonization of spatial strategies for the metropolitan areas. These could define the influence areas – territories and localities – that surround an urban centre and are directly influenced by the city’s evolution and by the interconditional and cooperation relationships that develop through economic activities, food supply, and access to social and commercial infrastructure, leisure infrastructure. The influence area’s dimensions are directly related to the size and functions of the pole urban centre. Law No.350/2001 also proposes an instrument for the protection of the environment that overlaps the metropolitan territories – The green bypass – “defined area around the capital of Romania and the first grade towns, in order to protect the environmental elements, to prevent uncontrolled extension of these towns and to ensure additional spaces for pleasure and repose”. Also at the level of metropolitan areas it is proposed the identification of some polycentric development systems called: Urban system – “system of neighboured localities that establish relationships of economic, social and cultural cooperation, of territory arrangement and environment protection, technical town equipping, each of them maintaining its administrative autonomy”. The law No. 215/2001 of local public administration, as well as the law No. 195/2006 of decentralization foresees the possibility of association among local authorities, without detailing the terms of such an association. Beyond these few legal marks, concerns regarding the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest get an important political connotation. A year and a half ago, the chief of the European Commission Delegacy to Bucharest, Jonathan Scheele, said that “Romania does not have a Capital that deserves to become part of the European Union. Ruined buildings, chaotic traffic and the lack of authorities’ vision on city’s development perspectives make Bucharest a capital that does not deserve to ntegrate among the European capitals” (Cristea, 2005). Meantime, Romania has integrated in the European Union, but the Capital’s problems are the same. The notion of metropolitan area has been around for over four years but it became strongly politicised and started a veritable competition for initiating different laws regarding the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest, without a real public debate and without tracking to obtain the best “grade” for the project viability, for how much it represents the interests of the most citizens and proposes a balanced development of the capital and the surrounding area. Meantime, there appeared a number of projects (legislative or not) that propose a certain structure for the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest, a geographical development and an administrative model for it.

Creation of the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest: advantages and disadvantages

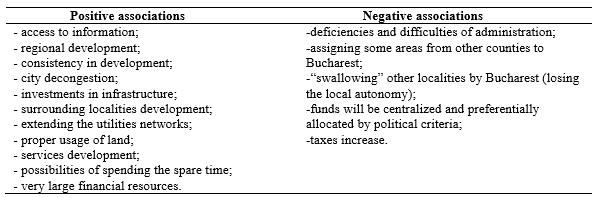

The advantages and disadvantages that the organisation of the MAB implies can be, at this level, inferred. After an inquiry made in 2005 by ALMA-RO Association (2006a) the interest developed by local institutional actors regarding the creation of the MAB was underlined, considering the process itself as a condition for “development”. ALMA-RO Association also associated this process with “infrastructure”, this being one of the weak points of the area around Bucharest. However, there are more positive and negative estimations, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Associations with the term of the MAB on behalf of local institutional actors (ALMA-RO Association, 2006a)

Among the institutional actors in Bucharest, the main advantages of the MAB are expected to be decongestion of the city, the urban agglomeration, on the one hand, and economic advantages that derive from the development of the area’s attractiveness for investors, on the other hand. The communities around Bucharest, especially the rural ones, expect that the MAB will advantage them due to the fact that:

- it would lead to the improvement of the technical and transportation town’s infrastructure;

- jobs will be created by bringing on investors, and

- the population’s standard of living would increase.

There are also a number of disadvantages anticipated by the institutional actors, both from Bucharest, and from surrounding areas. For Bucharest, the main disadvantage is represented by the appearance of some speculative tendencies on the real estate market that will lead to a burst of land prices. Other disadvantages perceived by the institutional actors from Bucharest are the insufficiency of public services (health services, for example), taking into consideration that the need of such services will grow as a result of the increase of inhabitants from around Bucharest. At the level of rural communities the negative effects of the MAB are environment degradation due to the development of residences and to the loss of local autonomy. A sustainable approach of improving the life quality in the metropolitan area will need an integrated action at social, economic, environmental, and spatial level in order to entail an improvement of welfare in the metropolitan areas as a whole. These inter-related aspects can be approached by creating an Integrated Regional Strategy for Sustainable Development, developed and accepted by different interested factors from public, private and associative sectors and accomplished by active participation of the public.

Conclusions

This research emphasizes the main aspects of creation, organization and management of Metropolitan Area of Bucharest. One of the most important conclusions of our study indicates that there is a significant preoccupation in Romania for the theoretical approach of metropolitan area, but the political interests undermine the practical efforts. In this respect, this paper shows that the specialists have already established a methodology of determining the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest, including different functional criteria. There are laws regarding the arrangement of territory and urbanism, as well. The positive and negative aspects of metropolitan area were responsibly identified. The current research offers a tri-dimensional approach of MAB: economic, social, and legislative. Regarding the economic dimension, MAB should consider the sustainable regional development by aiming some major objectives: balancing the metropolitan spatial structure; improving the life quality in urban space; maintaining the regional identity, by capitalizing on the cultural patrimony; integrating management through the cooperation of regional infrastructure networks; creating new planning and implementation partnerships. The social aspects implied by the development of the metropolitan areas must face the demographic problems. In this way, the key issue becomes the external and internal migratory features, especially due to the migration from the nucleus city towards suburbs and surroundings. The legal dimension of MAB reveals that there are laws, which define the concepts implied by the process of creating the metropolitan area; on the other hand, the law does not propose forms of managing the metropolitan plan, forms of monitoring and controlling the area metropolitan development. All these sides disclose the fact that the development of Bucharest and of its surroundings is without doubt a result of an unstructured process. Such an evolution needs a proper planning, requires the correction of possible negative effects by legislative, scientific and management interventions, desires the optimization of the process, and, therefore, leads to the improvement of the quality of inhabitants’ life in such an area.

References

- Abraham D. (1991) Introducere in sociologia urbana. (Introduction to Urban Sociology) Editura Stiintifica, Bucuresti.

- ALMA-RO Association (2006a) Zona Metropolitană Bucureşti – Ghid de informare pentru autorităţile publice locale, Bucharest.

- ALMA-RO Association (2006b) Zona Metropolitanã Bucureşti – o provocare pentru administraţia publicã (The Metropolitan Area of Bucharest – a challenge for the public administration). Final report, Blueprint International.

- Arias A., Borja J. (2007) Metropolitan cities: Territory and Governability, the Spanish Case. Built Environment, Vol. 33, Issue 2, pp. 170-184.

- Barnes, W., Ledebur L. C. (1993) All in it Together: Cities, Suburbs and Local Economic Regions. Washington, DC: National League of Cities.

- Bautista J., Pereira J. (2006) Modeling the problem of locating collection areas for urban waste management. An application to the metropolitan area of Barcelona. Omega, Vol. 34, Issue 6, pp. 617-629.

- Brueckner J. K. (2000) Urban sprawl: Diagnosis and remedies. International Regional Science Review, Vol. 23, Issue 2, pp. 160-171.

- Cristea I. (2005) Jonathan Scheele: Bucurestiul nu are faţă de UE (Jonathan Scheele: Bucharest don’t fit with EU). Jurnalul National (Romanian newspaper), December 9, available at http://www.jurnalul.ro/index.php?section=rubrici&article_id=31700.

- CURS (2003) Studiu de fundamentare ştiinţifică a zonei metropolitane Bucureşti. Research Report for Local Administration of District 1, Bucharest.

- ESPON Project (2002-2004). The role, specific situation and potentials of urban areas as nodes in a polycentric development. Available at: http://www.espon.eu.

- Gao X., Asami Y. (2007) Effect of urban landscapes on land prices in two Japanese cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, Vol. 81, Issue 1-2, pp. 155-166.

- Gherasim V. (2005) Bucureşti, provocările istoriei şi expansiunea metropolitană, Bucharest.

- Hall P., Hay D. (1980) Growth centres in the European urban system. Geog. Dept., Reading University, U.K.

- Heyns W., Schoeman C.B. (2006) Urban congestion charging: Road pricing as a traffic reduction measure. WIT Transactions on the Built Environment, Vol. 89, pp. 923-932.

- Institutul Naţional de Statistică (1998-2008) Statistici lunare (National Institute for Statistics – Monthly Statistics). Available at: www.insse.ro.

- METREX (2004-2005) Interim Report on the PolyMETREX plus project. Towards a Polycentric Metropolitan Europe. Available at: http://www.eurometrex.org.

- METREX (2005) Integrated Metropolitan Strategies. Exploratory Discussion Note, June 2005.

- – -Pujol D., Domene E. (2006) Evaluating the environmental performance of urban parks in Mediterranean cities: An example from the Barcelona Metropolitan Region. Environmental Management. Vol. 38, Issue 5, pp. 750-759.

- Prato T. (2001) Multiple attribute evaluation of landscape management, Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 60, Issue 4, pp. 325-337.

- Rojas-Caldelas, R., Venegas-Cardoso, R., Ranfla-Gonzalez, A., Pena-Salmon, C. (2007) Planning a sustainable metropolitan area: An integrated management proposal for Tijuana-Rosarito-Tecate, Mexico. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, Vol. 102, pp. 33-42.

- Romanian Statistical Yearbook, 2006.

- The Law No. 195/2006 of decentralization (Legea 195/2006 a descentralizării).

- The Law No. 215/2001 of Local Public Administration (Legea 215/2001 privind Administraţia Publică Locală).

- The Law No. 350/2001of the territory arrangement and urbanism (Legea 350/2001 privind Amenajarea Teritoriului şi Urbanismului).

- The Law No. 351/2001, regarding the approval of the National Territory Arrangement Plan, the 4th section The Localities Network (Legea 351/2001, privind aprobarea Planului de Amenajare a Teritoriului Naţional, secţiunea a IV-a, reţeaua de localităţi).