Žilionis V. (2008). Gender differences in perception and use of Internet. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 46-53. ISSN 2029-0365. [www.ScholarArticles.net]

Author:

Vaidas Žilionis, Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

Abstract

Genders differences in wide scope of fields are investigated by many researchers. Analysis of literature shows that use of Internet, which is one of the most outstanding symbols of modern society, is gender-biased as well. The paper aims to research differences between males and females’ perception and use of Internet, including computer use abilities. First part of the paper reviews literature on gender differences in Internet perception. Second part deals with males and females’ experiences in Internet use, including computer anxiety and shopping online.

Introduction

Gender can be defined as a set of social and cultural norms and practices that the society prescribes to perform for human individuals according to their sex (Goroshko, 2005). Dholakia and Kshetri (2003) cite Fischer and Arnold, who maintain that gender-related constructs have been used at three levels: sex, gender identity and gender role attitudes. Sex is identified as physical or biological characteristic, while gender identity and gender role attitude are considered to be culturally and socially determined. It is noticed that males and females’ psychology is dissimilar regarding to certain aspects. Men and women rather differently perceive various social phenomena and often react to certain situations in distinct ways. In wide scope of fields many researchers try to find out why do these differences between genders exist and what factors influence them.

Analysis of literature shows that use of Internet, which is one of the most outstanding symbols of modern society, is gender-biased as well. According to Whitaker (2005), gender-based differences in attitudes towards Internet may be considered as an outcome of the socialization process. Ono and Zavodny (2002), citing Edwards and Wajcman, propose that Internet itself can be seen as a product of social relations and therefore diffusion of new innovations favours particular social groups. Males and females as social groups perceive Internet and their relation with it differently (Rabasca, 2000). Moreover, according to Hargittai and Shafer (2006), the literature on gender and computer use finds that females and males differ significantly in their attitudes towards their computer use abilities. The paper aims to reveal differences between males and females in perception and use of Internet, including computer use abilities.

Gender differences in perception of Internet

Dholakia et al. (2003) highlight that males and females have different “cultures”, are “specialized” in different tasks, and have different preferences. Such differences tend to interact with the features found in the Internet in ways that intensify their perceived usefulness and the perceived ease of use in favour of males rather than females. Internet is not culturally neutral or value-free. The values of most of the computer-based products and services tend to be more masculine than feminine (Dholakia et al., 2003; Bimber, 2000). Some theorists argue that male values have been institutionalized in the computer-based technology through its creators, embedding a cultural association with masculine identity in the technology itself (Bimber, 2000). In general, Rabasca (2000) maintains that females and males understand technology differently. Females talk about technology as a tool to do things with, using it to create, although males talk about it as a kind of weapon, the power it gives them. Females ask technology for flexibility, males ask it for speed. Females talk about using it to share ideas, males talk about the autonomy it grants them (Rabasca, 2000). Males speak more about technologyrelated topics (e.g., computers or cars), they have tendency to deny their feelings, including sadness (Huffaker and Calvert, 2004), while female conversations contain more graphical accents, more emotional subject matters (Lee, 2003; Huffaker and Calvert, 2004). Females’ Internet usage also tends to focus on verbal activities such as sending e-mail or visiting chat rooms rather than activities that help them understand technology or build visual spatial skills (Rabasca, 2000). Rabasca (2000) maintains that gender differences are reinforced by the Internet, as well as by computer software and games, which are typically targeted at traditional male interests, such as action-related sports, games and computer programming. In comparison, few Internet or computer games or software programs target females. Although the gender gap in Internet adoption has been diminishing over time (Dholakia et al., 2003), males have long been associated with computer-based technology while females have often been depicted as somewhat passive users (Slyke et al., 2002). In the case of the Internet, several technology-related factors tend to favour male users, including stereotyped views of female users, male-oriented aggressive formats of computer games, largely male-oriented online discussion groups, lacking elements of civility and online etiquette that females’ desire, low number of females in technology’s power positions (Dholakia et al., 2003). Nevertheless Teltscher (2002) believes that the stereotype about a young male as a typical Internet user changes rapidly in some countries, and slower in others.

Experience of using computers and Internet

Males tend to be more interested in computers than females, on average, contributing to gender differences in Internet use (Ono and Zavodny, 2002). According to Seybert (2007), in nearly all European countries and in all age groups, however, males are more regular users of both computers and the Internet than females and many more males than females are employed in computing jobs throughout the European Union (EU).

Figure 1. Females and males having used a computer or Internet on average once every day or almost every day in the last 3 months in the EU-25, 2006 (% of females/males in each age group) (Seybert, 2007)

Figure 1 represents that males are heavier users of computer and Internet than females. The difference between the proportion of young females (62%) and young males (67%) in the EU25 using computers daily in 2006 was relatively small. Differences in computer usage were greater between females and males in the age groups 25–54 and 55–74. Slightly more young males (53%) than young females (48%) used the Internet daily. A much smaller proportion of older people used the Internet and there were larger differences between females and males. Only 9% of females aged 55–74 used the Internet daily compared to 18% of males (Seybert, 2007).

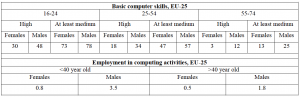

One plausible explanation of gender gap in Internet use is that differences exist between males and females in their socio-economic status (Bimber, 2000). Sex-role is first formed within the family, wherein norms are internalized. So, attitudes are learned and a self-image is acquired. Later, these behaviours are shaped and reinforced in the scholastic environment and in the workplace where society’s underlying culture is transmitted. Gender differences in attitudes towards Internet may ultimately be a reflection of differing social-cultural expectations and experiences (Whitaker, 2005). According to Rabasca (2000), society is inadvertently steering females away from computer technology. Among other sources of gender bias in Internet adoption, Dholakia et al. (2003) distinguish sociocultural factors, females’ involvement in decision-making, influence of culture on attitudes towards acquiring technology-related skills, features included in the Internet and attractiveness of alternative technologies. Education, income, and job status are associated with Internet use as well. Usually computers are expensive and not all households can thus afford buying them. Besides, as Hafkin (2002) stresses, females’ work is paid less than males. Also since females tend to stay at home, public entities that offer Internet access, such as schools, universities, Internet cafés and community centres are also often less accessible to females, especially those who are excluded from basic and higher education and who may for cultural and religious reasons have less access to public places (Teltscher, 2002; Ono and Zavodny, 2002; Hafkin, 2002). It is important to mention that female workers are not at a disadvantage relative to males with regard to computer use or skills; the same is true of non-working females relative to nonworking males, although both groups of females are generally less likely to use the Internet than comparable males. Further, females in non-standard jobs – part time positions or self-employment – do not have systematically lower levels of IT use and skills than comparable males (Ono and Zavodny, 2004). Besides, according to Seybert (2007), more males than females have basic computer skills and relatively many more males than females are employed in computing jobs (see Table 1). It is important to highlight that there was no change in the share of females employed in computing jobs in 2001-2006.

Table 1. Proportion of females and males by age and level of basic computer skills and employment in computing activities, 2006 (according to Seybert, 2007)

Computer anxiety. Use of computers and Internet is more attractive for users that have enough experience with these issues. The lack of experience may be the main reason of computer anxiety. According to Hargittai and Shafer (2006), females’ lower self-assessment regarding their computer use skills may affect significantly the extent of their online behaviour and the types of uses to which they put the medium (Hargittai and Shafer, 2006).

As long as the society usually views computer use as masculine, females are simply not expected to become comfortable with computer use as readily as males. Females generally display less confidence and more discomfort using computers (Hargittai and Shafer, 2006). Indeed, it has been argued that the gender gap in male-dominated fields such as science and technology may be at least partly due to computer anxiety, as higher levels of computer anxiety would lead females to simply self-select out of these careers to begin with. Many studies have demonstrated that females report higher levels of computer anxiety than males. Computer anxiety has generally been conceptualized as a fear related to the use of computers, or feelings of intimidation and hostility towards this form of technology (Whitaker, 2005). Computer anxiety can be related with losing privacy. It is confirmed by Garbarino and Strahilevitz (2004) that females are more concerned than males with losing their privacy both in Internet contexts and non-Internet contexts. Besides, according to Croson and Gneezy (2004), the common stereotype is that females are more risk averse than males.Therefore, computer anxiety is more common to females and as a reason can be related with lack of Internet use experience. As one type of Internet experience, shopping online is analysed in the paper. Shopping online. Although females account for well over 70% of all purchases made in more traditional “off-line” purchase environments, such as retail stores and catalogues, females have been found to be less likely than males to buy online and have also been found to spend less money, on average, online (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004). Recent evidence on types of online shoppers suggest females dominate the “click and mortar” types who shop online but buy offline while male shoppers dominate the “hooked” and “hunter-gatherer” types who use online shopping the most (Dholakia and Kshetri, 2003). One possible explanation for the gender gap in online purchasing is that females are more concerned than males with the risks of buying online (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004). Females need for tactile input compared to males in making product evaluations (Citrin et al., 2003). Specifically, females have been found to perceive greater risks in a wide variety of domains including financial, medical, and environmental (Garbarino and Strahilevitz, 2004). It is rather surprising, that e-shopping, except for health and apparel, is dominated by males (Dholakia and Kshetri, 2003). Shopping online usually is also dominated by males. Females are tended to buy in usual purchasing environment. It leads such factor as avoidance of the risk and need for tactile input. Therefore I can state that the key factor for experience of Internet use is that females do not want to take any risk. They like to feel safe and usually avoid new experience.

Conclusions

Gender differences in Internet use are reinforced by several socio-economic reasons. At first, society has stereotypes that computer-based technology is created to males. Secondly, males’ attitude toward computer use is more friendly comparing with females’ one. And the third, gender has different access to computer as well as Internet conditioned by education, income, job status and even religion or culture. Females and males differently perceive Internet as one of the kinds of technology. Females consider technology as a tool to do things with, to share ideas, although males see it as a kind of weapon, the power it gives them. Usually females express more emotions using Internet and they are not tended to take a risk. These influence such with experience related things as computer anxiety and shopping online. Females are more likely to have computer anxiety than males. It can be conditioned by less experience with computer use and also that Internet is more attractive and more convenient to use to males. Males dominate in shopping online as well. This is related to the fact that females tend to avoid risk and wish to buy tactile things. Therefore it can be stated that gender differences in Internet perception and use are influenced by psychological aspects, dissimilarities in socioeconomic situation as well as prevailing masculine features of computer technologies and Internet.

References

- Bimber B. (2000) Measuring the Gender Gap on the Internet. Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 3, pp.

868-876. - Citrin A. V., Stem D. E., Spangenberg E. R., Clark M. J. (2003) Consumer need for tactile input: an internet retailing challenge. Journal of Business Research, No. 56, pp. 915-922.

- Dholakia R. R., Dholakia N., Kshetri N. (2003) Gender and internet usage. The Internet Encyclopedia, edited by H. Bidgoli, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Dholakia R. R., Kshetri N. (2003) Gender asymmetry in the adoption of internet and e-commerce [interactive], available at: http://www.crito.uci.edu/noah/HOIT/HOIT Papers/Gender Asymmetry.pdf.

- Garbarino E., Strahilevitz M. (2004) Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. Journal of Business Research, No. 57, pp. 768-775.

- Goroshko O. (2005) Netting Gender [interactive], available at http://www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/russcyb/library/texts/en/control_shift/Goroshko.pdf.

- Hafkin N. (2002) Gender Issues in ICT Policy in Developing Countries: An Overview // United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW) Expert Group Meeting on “Information and communication technologies and their impact on and use as an instrument for the advancement and empowerment of women” Seoul, Republic of Korea, 11-14th November 2002. EGM/ICT/2002/EP.1, [interactive], available at http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/ict2002/reports/Paper-NHafkin.pdf.

- Hargittai E., Shafer S. (2006) Differences in Actual and Perceived Online Skills: The Role of Gender. Social Science Quarterly, June, 2006.

- Huffaker D. A., Calvert S. L. (2004) Gender, Identity and Language Use in Teenage Blogs. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 10, Issue 2 [interactive], available at: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/huffaker.html.

- Lee Ch. (2003) How Does Instant Messaging Affect Interaction Between the Genders? [interactive], available at http://www.stanford.edu/class/pwr3-25/group2/pdfs/IM_Genders.pdf.

- Ono H., Zavodny M. (2002) Gender and the Internet. SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, No. 495 [interactive], available at: http://www.frbatlanta.org/filelegacydocs/wp0210.pdf.

- Ono H., Zavodny M. (2004) Gender Differences in Information Technology Usage: A U.S. – Japan Comparison. Working Paper 2004 – 2 [interactive], available at: http://www.sidos.ch/method/RC28/abstracts/Madeline Zavodny.pdf.

- Rabasca L. (2000) The Internet and computer games reinforce the gender gap. Monitor on Psichology, Vol. 31, No. 9 [interactive], available at: http://www.apa.org/monitor/oct00/games.html.

- Seybert H. (2007) Gender differences in the use of computers and the Internet. Statistics in Focus: Population and Social Conditions, No. 119/2007, p. 7. ISSN 1977-0316.

- Slyke C. V., Comunale Ch. L., Belanger F. (2002) Gender differences in perceptions of web-based shopping. Communications of the ACM, Vol. 45, No. 7, pp. 82-86.

- Teltscher S. (2002) Gender, ICT and Development. Background note to the presentation given at the World Civil Society Forum, Geneva, 14-19th July 2002, [interactive], available at http://www.worldcivilsociety.org/documents/17.13_teltscher_susanne_unctad.doc.

- Whitaker B. G. (2005) Internet-based attitude assessment: does gender affect measurement equivalence? Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 31, No. 9 [interactive], available at www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh