Golubevaitė L. (2008). Eco-labelling as a marketing tool for green consumerism. Global Academic Society Journal: Social Science Insight, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 25-36. ISSN 2029-0365. [www.ScholarArticles.net]

Author:

Loreta Golubevaitė, Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania

Abstract

“Going green” has become the most topical and fashionable trend during the last decade. Many companies throughout the world have claimed their ecological responsibility and rushed to implement desires of constantly increasing community of green consumers. The aim of the article is to reveal importance of eco-labelling as a marketing tool for green consumerism. The article provides an exhaustive profile of typical green consumer. It analyses the whole spectrum of environmentally related “consumer colours” basing on findings of such authors as Torjusen et al. (2004), Bibbings (2003) and Newell (2001); draws profile of green consumer basing on definitions from Peattie (2001a), Zarnikau (2003), Bui (2005) and Ryan (2006); and generalizes the most common characteristics and behavioural features of this consumer group. Researches show, that eco-labelling is a crucial factor in customer choice on purchasing environmentally friendly products. Eco-label verifies the ecological features of products and thus is an important marketing tool for reaching green consumers. World-wide examples of eco-labels are given in this article. However, businesses must keep in mind that improper application of ecolabelling may cause the opposite effect. Therefore, importance of marketers‟ communication with green consumers are emphasised in this article.

Introduction

In the late 1980s many manufacturing and retail companies experienced a dramatic change in consumers‟ tastes, in favour of products with less impact on the environment. The first signs of interest in green marketing could be seen in the 1970s but it was not until the late 1980s and the 1990s that environmentally friendly or ecological marketing gained attention from broader audience. Researchers argued for a rapid growth in the use of ecological products which represented a shift in consumer behaviour (Hess and Tim, 2008). During this wave of green consumerism firms realized that they could increase their profits by taking environmental concerns seriously (Eriksson, 2004). Therefore interest in green consumerism and green marketing grows more and more. The aim of the article is to reveal importance of eco-labelling as a marketing tool for green consumerism. The green consumer has been the central character in the development of green marketing, as businesses attempt to understand and respond to external pressures in order to improve their environmental performance (Peattie, 2001a), as well as respond to consumers‟ willingness to pay a premium to “protect the environment” (Mason, 2006). Therefore, green marketing, or marketing strategies that “appeal to the needs and desires of environmentally concerned consumers” are of special interest (Mathur and Mathur, 2000). Even, referring to Eriksson (2004), green consumerism can significantly replace environmental regulation. Referring to the above mentioned changes in the market, the paper deals with two questions: (1) how green behaviour (consumerism) is evidenced, and (2) how to profit from the changes in customer‟s behaviour by using tools of green marketing.

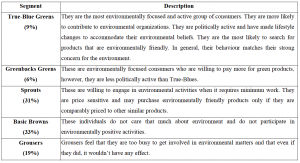

Green consumerism The scope of the meaning of green is substantial. It can relate to issues such as ecological concerns, conservation (planet and animals), corporate social responsibility, humanitarian concerns, fair trade, clean water, animal welfare, equality, and sustainability (Saha and Darnton, 2005). However, Torjusen et al. (2004) highlight that green should be distinguished from ethical consumption, where green consumerism is used as referring to consumer concern and action for environmental issues, while ethical consumerism is understood as concern for social issues reflected through consumer choices, for example through support of fair-trade goods. Various studies have attempted to divide consumers into different types – ranging from the non-environmentalist grey consumer who is sceptical about environmental issues and happy to trust science to solve any problems; to the committed deep green consumer who integrates environmental considerations into his / her every lifestyle decision. Usually green consumers may be considered as such customers who act towards the environment through purchasing large amounts of eco-friendly goods (Torjusen et al., 2004; Bibbings, 2003). Referring to Ginsberg and Bloom (2004), 58% of U.S. consumers try to save electricity at home, 46% recycle newspapers, 45% return bottles or cans and 23% buy products made from, or packaged in, recycled materials. Therefore, green products should be non-toxic, energy efficient, made using renewable materials, maintain the viability of the ecosystem and community, made from non-renewable materials previously extracted, durable and reusable, easy to dismantle, repair, and rebuild, appropriately packaged for direct distribution (Seele, 2007). Seeking to distinguish the main characteristics of green consumer, Newell (2001), Ginsberg and Bloom (2004) grouped customers into 5 segments (see Table 1). Ginsberg and Bloom (2004) gives proportions of each segment in the society. According to these authors, the five segments however cover 98 per cent of population. The rest 2 per cent remain unassigned to any of the categories below.

Table 1. Segments of customers according to their approach to environment (Newell, 2001; Ginsberg and Bloom, 2004)

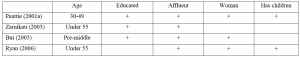

According to McDonald and Oates (2006), two factors making significant impact on perception of equal green and non-green (or grey) purchases are: degree of compromise, and degree of confidence (see Figure 1). In Figure 1, the matrix brings these two key variables that affect the likelihood of any purchaser (whatever is the intensity of his / her environmental concern – or shade of green) being influenced by environmentally related criteria when considering a purchase: the degree of compromise involved and the degree of confidence generated in the environmental benefits of a particular choice. The degree of compromise may take a variety of forms such as having to pay more, or travel further in order to purchase a green product; and the degree of confidence assure the consumer that the product addresses a genuine issue and that it represents an environmental benefit.

Figure 1. The green purchase perception matrix (Peattie, 2001a; Peattie, 2001b; McDonald and Oates, 2006)

Figure 1. The green purchase perception matrix (Peattie, 2001a; Peattie, 2001b; McDonald and Oates, 2006)

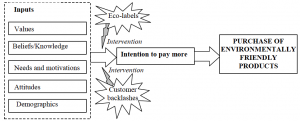

Green consumers usually understand themselves as being environmentally friendly consumers. Lately, more people make their homes energy efficient, drive more fuel efficient cars, focus more on recycling, and buy products that are healthier and less harmful to society and the environment (Ryan, 2006). According to Bui (2005), in regards to the effects of environmental attitudes on behaviour, findings suggest that attitudes and values are the most consistent predictor of pro-environmental purchasing behaviours. At first, green consumer should value protecting the environment before they can have the intention of buying environmentally friendly products. Table 2 generalizes description of the typical green consumer offered by Peattie (2001a), Zarnikau (2003), Bui (2005) and Ryan (2006). Typical green consumer can be described as premiddle aged, well-educated, affluent woman, usually politically liberal (Peattie, 2001a).

Table 2. Characteristics of typical green consumer

Typical green consumer is able to pay a premium for eco-friendly goods. However, even among members of the least affluent social class the majority attached some importance to the issue of recycling, and it would be wrong to assume that all green consumers are well-off (Bibbings, 2003). The sustainable or green lifestyle is often perceived to be more expensive and difficult. Most consumers however consider factors of price and convenience first and foremost. They are distrustful of eco-claims on products and there is a need for an over-riding, reliable source of information about the sustainability of products and services (Bibbings, 2003). Consumers making green purchases are motivated by health issues (buying organic food), mental values (green choices as manifestation of self-expression and personal identities, “distinction”) and quality of life issues (morally guided decisions, e.g. green product choices, which harm the environment less than the conventional ones) (Haanpää, 2005). Referring to Gilg et al. (2005), green consumer tends to: (1) purchase products, such as detergents, that have a reduced environmental impact; (2) avoid products with aerosols; (3) purchase recycled paper products (such as toilet tissue and writing paper); (4) buy organic produce; (5) buy locally produced foods; (6) purchase from a local store; (7) buy fairly traded goods; (8) look for products using less packaging; (9) use one‟s own bag, rather than a plastic carrier provided by a shop. Green consumerism brings new market of environmentally friendly consumers. Therefore companies face the challenge to expand new market niches and to meet customers‟ needs. Companies require new marketing tools that help to reach the environmentally friendly customers.

Eco-labelling as a marketing tool

Drucker, back in 1960, described consumerism as challenging four key assumptions about marketing and these are worth revising in relation to the green challenge (Peattie, 2001a):

- Consumers know their needs.

- Businesses care about these needs and understand how to meet them.

- Businesses provide useful information to allow consumers to match products to needs.

- Products and services deliver what consumers expect and what businesses promise.

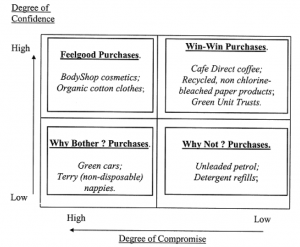

Furthermore, the findings from other authors showed an increased demand for green products from consumers and that people were inclined to pay additional costs for environmental friendly characteristics (Hess and Tim, 2008). Businesses realize that they must be prepared to provide their customers with information on the environmental impact of their products and manufacturing processes (Ginsberg and Bloom, 2004). Although the “win–win” logic of being green and competitive is disputed in the literature, it may be pointed to external benefits that arise from environmental improvement, including increased sales, improved customer feedback, closeness to customers, enhanced competitiveness and improved corporate image (Pujari et al., 2003). According to Bui (2005), input (i.e. values, beliefs/knowledge, needs, motivations, attitudes, demographics) and intervening variables (i.e. eco-labels and consumer backlash) usually drive choice of green purchases (see Figure 2). Therefore marketers should pay greater attention to these inputs and interventions that affect process of customer choice.

Figure 2. Process of customer choice on purchasing environmental friendly products (Bui, 2005)

Marketing activities, which attempt to reduce the negative social and environmental impacts of existing products and production systems, and which promote less damaging products and services, are considered as green marketing (Peattie, 2001b). Four categories of green marketing might be distinguished. These are: green products, recycling, green promotions, and appointments of environmental policy managers (Mathur and Mathur, 2000). If properly implemented, green marketing may help to increase the emotional connection between consumers and brands (Ginsberg and Bloom, 2004). Environmental or green marketing has been seen as a tool towards sustainable development and satisfaction of different stakeholders. Green marketing may be seen as “the holistic management process responsible for identifying, anticipating and satisfying the requirements of customers and society, in a profitable and sustainable way” (Kärnä et al., 2003). Firms green their products/policies because they wish to be socially responsible – as these are the “right or ethical things to do”. Such policies may or may not generate quantifiable profits in the short run. However, in the long run, socially responsible policies are more likely to have economic payoffs (Prakash, 2002). Interestingly, a survey found that for 70 per cent of the respondents, purchase decisions were at least sometimes influenced by environmental messages in advertising and product labelling (D‟Souza, 2004). Eco-labelling is intended to facilitate green consumerism, wherein a consumer who values the product attribute of “environmental quality” significantly can express this preference through product selection and purchase. Green marketing should be informative and accurate, therein raising consumer awareness, improving the sales of green alternatives and thereby improving overall environmental quality (Hussain and Lim, 2001). Eco-labelling identifies environmentally preferable equipment within a product range and thereby helps to reduce consumer confusion concerning sustainability indicators (Williams, 2008). Consumers must know and trust a label before they can use it to make purchasing decisions. Eco-labels have emerged as the main marketing tool, since green marketing was introduced in the 1990s (Hess and Tim, 2008). An integrated marketing communications approach and/or a holistic approach, using eco-labels, may better educate consumers on the social and environmental impacts of their purchasing decisions (Bui, 2005). Eco-labelling has become the main tool to verify the ecological features of products (Hess and Tim, 2008). Eco-labelling, that is the certification of products that have a lower environmental impact compared to like counterparts in the same product category, is not a policy tool. Eco-labelling is a voluntary process, and the criteria fulfilment is neither legislated nor regulated (Williams, 2008). The Mobius loop – the symbol for recycling – is on products everywhere, without an accompanying explanation of whether the product can be recycled or is made from recycled materials (Bibbings, 2003). Consequently, as green consumers emerged so did environmental labels and marketing claims for example: eco-friendly, environmentally safe, recyclable, biodegradable and ozone friendly (D‟Souza, 2004). There are different labels of eco-friendly or environmentally safe products in the world (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Examples of eco-labels in the world

Figure 3. Examples of eco-labels in the world

According to Wigder (2008), not all eco-labels have the same impact. In fact, consumers indicate that they are more likely to make eco-friendly purchase decisions if the eco-labels are also widely recognized and trusted brands themselves. Familiar labels for programs like the EPA‟s Energy Star have more significant influence on consumer behaviour than others. Eco-labels influence consumer behaviour in two ways. First, they introduce green as a considered attribute at the point of sale. Second, they enable consumers to comparison shop based on green (Wigder, 2008). For instance, HP Company (Hewlett-Packard) uses eco-labels for eco highlights on package of the products (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Eco Highlights of Hewlett-Packard product

Figure 4. Eco Highlights of Hewlett-Packard product

Although eco-labels help consumer to identify green products easier, marketers should pay attention that flimsy and exaggerated eco-claims have led many consumers to become increasingly distrustful and cynical (Bibbings, 2003). Every effort should be taken for eco-label to represent real features of product. According to Bui (2005), the importance of environmental issues can motivate consumers‟ environmental behaviour. Therefore, marketers should communicate to the target audience that buying green products could have a significant impact on the welfare of the environment. Despite this, marketers should remember that consumers are willing to spend extra money for a socially desirable concept like environmentalism, but purchasing data suggest that green matters very little when compared to price, quality and convenience. Green consumers are looking for green thinking to be ingrained across the value chain – from product development to distribution. Sceptical consumers can quickly discern between companies with legitimate green strategies, and those who are impostors. It‟s usually immediately evident when the only green thing about a company is their logo and marketing materials (Leishman, 2008). Firms can green themselves in three ways: value-addition processes (firm level), management systems (firm level) and/or products (product level) (Prakash, 2002). Going green, companies should follow principle of 3R (Xiao-di and Tie-jun, 2000):

- reduce of waste: using relatively less raw material and energy to reach the designated goal of production so that from the very beginning great attention is paid to saving energy and eliminating (or reducing) pollution.

- reuse: products and packing material should, as long as possible, be capable of being repeated use in their original forms for energy saving and environmental protection.

- recycling: after the products have been out of use, they should be of being recycled for reuse.

Going green often means reducing waste – this can actually have a positive impact on the bottom line in addition to providing valuable stories to fuel marketing messaging. Giving out fewer napkins, using less ink and paper, encouraging customers to use online billing – these are all green initiatives that can quickly reduce company costs (Leishman, 2008). Greening the value-addition processes could entail redesigning them, eliminating some of them, modifying technology and/or inducting new technology – all with the objective of reducing the environmental impact aggregated for all stages. For example, a steel firm may install a state-of-the-art furnace, thereby using less energy to produce steel (Prakash, 2002). New technologies, however, may allow firms to better target existing green consumer segments. For instance, the Internet allows ecologically minded firms to target green consumers globally without developing extensive distribution networks (Polonsky and Rosenberger III, 2001). As an example of internet-facilitated green movement, greenzer.fr is an internet portal dedicated exclusively to green goods. Seeking for success in labelling of green products, firms should promote green consumerism so that consumers understand benefit of environmental friendly products, and should try to involve new consumers into green movement. In such case, being labelled as a green company may generate a more positive public image, which can, in turn, enhance sales and increase stock prices. A green image may also lead consumers to have increased affinity for a company or a specific product, causing brand loyalty to grow (Ginsberg and Bloom, 2004). Green as a label on the other hand is attributed not only positive: the media controls and accuses misuse and corporate scandals (Seele, 2007). In order to be named a green company, eco-labelling alone is not enough. It is also required that company was green in day to day activities and actively supported the movement of green consumerism.

Conclusions

Recent emergence of green trends has created a brand-new generation of environmentallyconcerned consumers and attracted attention of many companies worldwide. Green consumers have brought new market niche for business. Although definition of green is rather fuzzy since it involves many different issues, the whole branch of marketing with the central figure – green consumer – has appeared on business stage. Researchers suggest grouping consumers into five segments of different shades according to their approach to environmental issues. Typical green consumer may be described as pre-middle aged, well-educated, affluent woman with children. However, despite of the consumer shades, the green purchase perception is based on degree of compromise and degree of confidence. Eco-labelling is known as one of the most popular tools of green marketing worldwide. Countries or regions have their own eco-labels, which help customers to identify environmentally friendly products. First of all, customers should trust the company offering eco-labelled products. Therefore, such company should be green in its everyday activities, i.e. to reduce the waste, reduce, and recycle; and, apart from this, to promote green consumerism actively in order to expand its market.

References

- Bibbings J. (2003) Consumption in Wales: Encouraging the Sustainable Lifestyle. Available at: http://www.wales-consumer.org.uk/research_policy/pdf/WCC13_Consumption_in_Wales.pdf.

- Bui M. H. (2005) Environmental marketing: a model of consumer behavior. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association of Collegiate Marketing Educators, pp. 20-28.

- D‟Souza C. (2004) Ecolabel programmes: a stakeholder (consumer) perspective. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 179-188.

- Eriksson C. (2004) Can Green Consumerism Replace Environmental Regulation?: A DifferentiatedProducts Example. Resource and Energy Economics, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 281-293.

- Gilg A., Barr S., Ford N. (2005) Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures, No. 37, pp. 481-504.

- Ginsberg J. M., Bloom P. N. (2004) Choosing the Right Green Marketing Strategy. MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 79-84.

- Haanpää L. (2005) Postmodern and structural features of green attitudes and consumption. National, European, Global. Research Seminars of Economic Sociology 2004. Series Discussion and Working Papers 2:2005, ISBN 951-564-280-9, pp. 29-52.

- Hess E., Tim P. (2008). Environmental friendliness as a marketing strategy. Available at: http://www.diva-portal.org/diva/getDocument?urn_nbn_se_hj_diva-1151-1__fulltext.pdf.

- Hussain S. S., Lim D. W. (2001) The Development of Eco-labelling Schemes. Handbook of Environmentally Conscious Manufacturing, pp. 171-188.

- Kärnä J., Hansen E., Juslin H. (2003) Social responsibility in environmental marketing planning. European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 37, No. 5/6, pp. 848-871.

- Leishman P. (2008) Green marketing – a primer. Available at http://www.torquecustomerstrategy.com/ files/publications/080217_torquepublication_greenmarketing_whitepaper_1204054125.pdf.

- Mason Ch. F. (2006) An economic model of ecolabeling. Environmental Modeling and Assessment, Vol. 11, pp. 131-143.

- Mathur I., Mathur L. K. (2000) An Analysis of the Wealth Effects of Green Marketing Strategies. Journal of Business Research, No. 50, pp. 193-200.

- McDonald S., Oates C. J. (2006) Sustainability: Consumer Perceptions and Marketing Strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 15, pp. 157-170.

- Newell S. J. (2001) Green advertising. Handbook of Environmentally Conscious Manufacturing, pp. 189-204.

- Peattie K. (2001a) Golden goose or wild goose? The hunt for the green consumer. Business Strategy and the Environment, No. 10, pp. 187-199.

- Peattie K. (2001b) Towards Sustainability: The Third Age of Green Marketing. The Marketing Review, No. 2, pp. 129-146.

- Polonsky M. J., Rosenberger III P., J. (2001) Reevaluating Green Marketing: A Strategic Approach. Business Horizons, September-October, pp. 21-30.

- Prakash A. (2002) Green marketing, public policy and managerial strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, No. 11, 285-297.

- Pujari D., Wright G., Peattie K. (2003), Green and competitive influences on environmental new product development performance. Journal of Business Research, Vol. 56, pp. 657-671.

- Ryan B. (2006) Green Consumers: A Growing Market for Many Local Businesses. Let„s Talk Business: Ideas of Expanding Retail and Services in Your Community. Available at: http://www.uwex.edu/CES/cced/downtowns/ltb/lets/LTB1106.pdf.

- Saha M., Darnton G. (2005) Green Companies or Green Con-panies: Are Companies Really Green, or Are They Pretending to Be? Business and Society Review, Vol. 110, Issue 2, pp. 117-157.

- Seele P. (2007) Is Blue the new Green? Available at: http://www.responsibilityresearch.de/resources/CRR+WP+03+seele+blue+green.pdf.

- Torjusen H., Sangstad L., Jensen K. O., Kjærnes U. (2004) European Consumers’ Conceptions of Organic Food: A Review of Available Research. Professional report no. 4-2004. Available at: http://www.organichaccp.org/haccp_rapport.pdf.

- Wigder D. (2008) Eco-labels Impact Consumer Behavior. Available at: http://marketinggreen.wordpress.com/category/eco-brands/.

- Williams W. (2008) Eco-labelling Technology – for you and the planet. Available at http://www.tcodevelopment.com/tcodevelopmentnew/Artiklar/Williams_GreenElectronics2008.pdf.

- Xiao-di Z., Tie-jun Z. (2000) Green marketing: A noticeable new trend of international business. Journal of Zhejiang University – Science A, Vol. 1 ,No. 1, pp. 99-104, ISSN 1009 – 3095.

- Zarnikau J. (2003) Consumer demand for „green power‟ and energy efficiency. Energy Policy, Vol. 31, pp. 1661–1672.